Ten years ago, on Dec. 14, 2012, a gunman entered Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, CT, with two rifles and a handgun and killed 20 students between the ages of six and seven and six adults. It is the deadliest mass shooting at an elementary school in American history and the fourth deadliest overall. The attack renewed calls for stricter gun laws and universal background checks. Below, Sarah D’Avino details the life-changing consequences of her sister’s murder, and how she has transformed her pain into recovery.

That morning, my mom drove me to a doctor’s appointment in West Hartford, as she did every week. Later, I was supposed to hang out with one of my girlfriends at my house. When mom and I got back home, my friend was already there. She looked shaken and told us, “I have to go! I can’t hang out today. I just got word there was a shooting at my nephew’s school.” That school was Sandy Hook Elementary.

My mom and I were in so much pain for her, seeing her look so distraught. We told her, “Go! Go! Go!” We go inside the house and turn on the news. We begin to hear aerial sounds above the house. Minutes later, Rachel’s boyfriend, Anthony Cerritelli, rushed into the living room—we all lived together—and he goes, “That’s Rachel’s school.” We thought Rachel was at Newtown Elementary School the entire time, but it was that very second we learned she had switched to Sandy Hook less than a week earlier.

Rachel had her master’s from Post University in behavioral therapy, was working on her doctorate in the same field from the University of St. Joseph, and was about to become a board-certified behavioral analyst. She was doing her clinical hours with one of the Sandy Hook students on the autism spectrum, seven-year-old Josephine Gay, who also died that day. Rachel’s job was to make the “mainstream” classroom inclusive for Josephine, accommodate her needs, and help her integrate with the other students.

After Tony tells us she’s at Sandy Hook, we panic when we don’t hear from Rachel. We looked at our phones repeatedly, hoping and waiting to hear from her. When we got no response, my mom drove us to the Town Hall. We weren’t there long before the police caravanned us across town to the firehouse, which became the official family meeting area. Then, one by one, we witnessed families being told their child wasn’t coming home. It was painful, especially not knowing what was happening with Rachel.

The shooting was at nine in the morning. By nine that night, we still had no word. At this point, it’s just my mom and me sitting at the fire station. Because Rachel was so new, her name wasn’t on any list. But the officers knew they had a family looking for a “Rachel D’Avino,” and they knew they had a body whose name they didn’t know, but they didn’t want to tell us anything until they were sure. Finally, an officer walks over to us. It must’ve been killing this man to watch us wonder all day. When he got to where we were, I assume he broke every protocol when he said, “Anybody who was in that school, and we don’t know who they are, is gone.” I collapsed on my mother. We screamed on top of each other. A priest came over, put his hands on us, and said a prayer. I grabbed his hand.

We left shortly after that and drove home to tell my younger sister, Hannah. I remember just taking deep breaths, clenching that steering wheel with all my might, and thinking, Just suck it up and get mom home. Then, around 2:30 in the morning—now it’s a Saturday—we get a knock on the door. There are police officers, social workers, and that same priest at our door. They hand us a packet on how to go about making funeral arrangements. That was our confirmation: Rachel had been identified by her tattoos.

That night, I had been clean four years: From 16 to 21, I abused substances, mostly opioids. After hearing the news, I didn’t know how to feel what I was feeling. So, I returned to what I knew — I relapsed and had a drink. What started as using to numb the pain after a few years became using against my will. In the 10 years since Rachel died, the first half was spent using to not feel, then there was about a year of using because I didn’t know how to stop. I was stuck in a cycle of active addiction, where I would watch myself, wish I wasn’t doing it, but not know how to stop. And finally, one day, I just put my hands up and said, God, either kill me or fix me because I can’t do this anymore. I found a 12-step program and committed to it. I worked very hard on recognizing patterns in my life and why I choose substances when I’m in pain. On Feb. 26, I will have four years completely clean and sober. I am in grief and trauma counseling and finally unclenching that steering wheel. If I had a magic wand, I would not change that process. I needed every single one of those stepping stones to be who I am today. I have a sponsor who tells me, “You can’t climb a smooth mountain.”

One week after the shooting, on Dec. 21, we held Rachel’s funeral at The Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, CT. I gave her eulogy. That was the most important thing I could do for her. I spoke about how—Rachel being the oldest of us three sisters—our foundation was rocked. The church was standing room only with a video camera doing live feed to the church hall because that was filled with people, too. The sign-in book from that day has 695 signatures, many of which just say the so-and-so family—so it was probably close to 1,000 who came to honor Rachel. It was beautiful to see how much she was loved and remembered.

For the first year after the shooting, I felt paraded around. There were memorials, trips to D.C., interviews, family and friends showing up at the house, and standing in front of cameras and reporters. I felt very exposed. Today, I’ll go through something painful, like a breakup, and my friends would say, “Wow, you talk so freely about your pain.” And I’ll tell them, “Well, you have to imagine what it’s like for your grief process to be on the 11 o’clock news.”

I believe the day Sarah left us, she became my guardian angel. I’ve survived overdoses where there was no medical explanation as to why. I was told since I was a teenager I’d never carry a pregnancy to term. Now, I’m a mom.

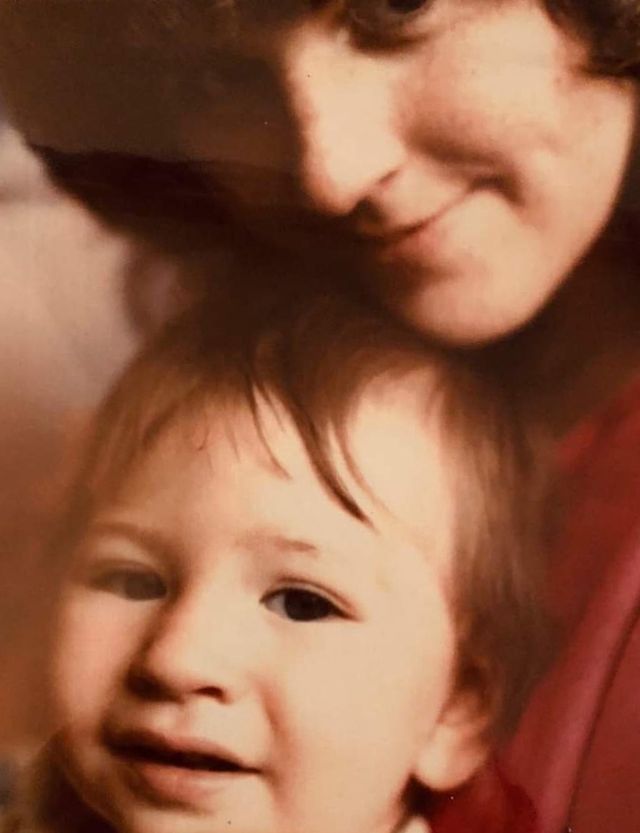

I’ve often thought about my relationship with Rachel and how my addiction and mental health issues drove a wedge between us. I wasn’t an easy sister to be around, and we didn’t get along, and I deeply regret that. There are no pictures of us past middle school. I regret that I can’t go back and fix our relationship. But what’s in my control now is how I apply the lessons from her loss to those still in my life: I document memories of myself and my loved ones; I will tell you I love you more; I will forgive faster; I will agree to disagree quicker. Because I can’t undo any of that with Rachel.

Growing up, Rachel was the ringleader. In kindergarten, her teacher called her one-gate Rachel because it didn’t matter if there was a fire drill or an ice cream truck outside, Rachel was only going at the pace Rachel wanted to go at. She remained that way into adulthood. She was bright and focused, an independent thinker who was always driven and always had a heart to help others, even before herself. I grieve for the loss of who Rachel would have become. I grieve for the children she would have had and the doting aunt she would have been. Rachel would’ve raised the world’s most well-rounded and highly self-esteem-possessing children. She would’ve had an opportunity to see who I’ve become. She would love this Sarah and want to spend time with me and tell me she loves me. It doesn’t just end with losing 29-year-old Rachel; it is a lifelong loss.

When my grandfather passed away, my grandmother gave me her engagement ring. It caused a bit of a stir between us because, as the oldest, Rachel felt it would be hers. A few months before she died, I don’t know why, but I put the ring by the coffee pot early one morning with a note that said Rachel, this always should have been yours. Love, Sarah. The ring had been missing a stone or two. Tony, her boyfriend, had the ring cleaned and replaced the stones. A few weeks before the shooting, he asked my mom and my stepfather for permission to propose to Rachel on Christmas Eve. She didn’t know. She would’ve said yes.

I once heard a quote that a person dies twice: Once when they take their last breath and the second time when their name is spoken for the last time. If that’s the case, Rachel is going to live forever. There are monuments in her honor, and she’s still a part of our family. Gregory, my 18-month-old son, knows he has an Auntie Rachel. She’s talked about just as much as any other family member. He’s been to her gravesite. We’ve told him stories about how she could sometimes be mischievous. How we’d put on a little play for our mom after dinner. Gregory may never meet his auntie, but he will always know her.

Throughout my grieving process, I’ve thought about my mother the most. Because, as a new mom, I’d look at my son and just get lost in my love for him. I would go hungry for him. I would go sleepless for him. But I only have the one. I could only imagine what it’s been like for my mom. When you have more than one child, there isn’t love more for any specific one of them, but there is that one that made you a mother. With Rachel’s death, my mom lost the child that made her a mother. I can’t even grasp what that would feel like, so that’s stayed with me.

In this 10-year grieving process, I’ve learned that it’s okay to hurt. It’s okay to feel pain. It’s okay to think nobody understands or that it’ll never go away. I’ve learned to not run away from grief and pain. That recovery is possible, that there’s no rock bottom with addiction, there’s just death. That hope is out there and doesn’t end until life does. I’m no longer afraid to admit that when Rachel died, yes, I turned to substances—it was the only thing I knew then to quench my pain. When life happens again, and it will, I know that I’m not exempt from grief and trauma and pain. None of us are. It is one of those hard-to-swallow pills of life. But now, I have a program of recovery, a toolbox of healthy coping skills, and a network of angels on earth to catch me. I know with all of my heart that Rachel is always protecting me, guiding me, and sending love and light my way.

I’ve also learned that trying to dull my pain with any substances only causes more, new, and different pain. I learned that the answer is not in a bag. The answer is not in a bottle. I did not find Rachel in any pill. I did not find her inside any needle. All that did was take me farther away from her memory. And now, being clean, being in recovery, living every day, one day at a time, for myself, I know that I am Sarah. I am not the things that have happened to my family and me. I am not the pain I’ve gone through. I don’t have to spend the rest of my life being Sarah, Rachel’s little sister who lost her to a tragic incident. I’m Sarah first, and it took 10 years to find this Sarah.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Rita Omokha is an award-winning Nigerian-American writer and journalist based in New York who writes about culture, news, and politics.