At the beginning of the pandemic, my editor and I used to fantasize about “the dad in the basement.” This was a father who, every morning of the pandemic, kissed his children goodbye and walked downstairs to his home office, where he worked uninterrupted all day long. He did not do Zoom calls with his children crawling on him; he did not have to push back his deadlines to wipe noses; he did not become overwhelmed with guilt and run upstairs to find out what all the yelling was about. No, this dad was in the basement. When he shut the door, he was at work. His work was important, and while he was doing it, nothing and no one could interrupt him.

The dad in the basement was an exaggeration — after all, few parents of any gender got a full day of uninterrupted work time during lockdown. But he was based on a real phenomenon — in one April 2020 survey, 80 percent of moms said they were responsible for the majority of remote schooling in their households. Only 45 percent of dads said the same. Another analysis found that moms spent an average of 8 hours a day on childcare in 2020 — the equivalent of an extra full-time job. Dads spent a little more than half of that.

The numbers only tell part of the story. The archetype of the dad in the basement captured something that my editor and I, and I’d wager many mothers of young children realized in the early months of the pandemic: our brains were no longer ours.

Of course, they tell you this will happen when you have a child. They say you’ll worry about them every second; when you’re with them you’ll wish you could get time to yourself, and when you’re away from them you’ll miss them horribly. When I had my son, though, I found these warnings not entirely accurate. I thought about him often when we were apart, and I certainly worried about him. But when I went back to work, I found that a small space opened, in which I could think and write, not precisely in the same way as I had before, but in a way that remained my own.

Then, of course, the pandemic happened. I was lucky enough to have a job in which I could work from home, and a husband who split childcare with me fifty-fifty, but that space — the physical place in which I was not primarily a mother — that was gone. I worked in my bedroom while my son laughed or screamed at my husband in the next room. When he cried, it was nearly impossible for me not to go to him, even though I knew his father was just as capable of soothing him.

Someone once told me that in our culture, an ideal mother is always available to her children, and it was all the easier to succumb to that stereotype when there was no physical separation between me and my child. At least when I was at an office there was a clear reason I couldn’t dry my son’s every tear; when we were at home together, if I didn’t comfort him — especially during a pandemic, a time of fear and stress for the entire world — I felt I must be a terrible person. It became almost impossible to concentrate on work during his waking hours. Like many parents working remotely during that time, I took to waking up before dawn so I could get things done while he slept.

My editor — also the mother of a small child — and I soon came to I resent the dad in the basement. When we heard about a man with such a setup, we shook our heads —up those basement stairs was a mom juggling the kids and her own job to make his privacy possible. And yet, we also envied him. Imagine being able to shut a door and just not think about your kid all day, we said. Imagine how much you could get done! We dreamed of it, or at least I did — some day in the distant future when, finally, I’d have the freedom to think only about work.

Then, bit by bit, the lockdown ended. My son went back to daycare. It wasn’t the same as before — now, childcare came with the ever-present threat of Covid, and I could never take for granted that it would be available the next day, the next month, the next year. Still, I was again able, much of the time, to complete a work assignment without stopping to soothe a tantrum.

Something had changed, however. The divided attention I’d experienced during lockdown — part of my mind on my writing and reporting, part of it on my son’s next snack or naptime — I no longer thought of it as entirely a bad thing.

Long before the pandemic, the writer Sarah Manguso described the way motherhood can consume and reorder the mind. “As I walk to the child’s room,” she wrote, “I’m already choosing which kind of fruit he’ll have with his morning toast.” Manguso also once said in an interview that since having her son, she was “a better person with a better life,” an expression of confidence and self-knowledge that has always been shocking to me. I do not know if I am a better person since having my son, or since going through lockdown with our family: probably not.

However, something did change in my mind after I worked in the house with my son at the beginning of the pandemic. I have not quite regained the single-minded focus I was able to access before lockdown began, and I’m not sure I want to. To be more precise: before the pandemic, I was sometimes, for days on end, able to work as though I did not have a child. I could be the dad in the basement. I do not want to be that man anymore. I do not want that for any of us.

Many sociologists and other scholars, as well as workers themselves, have pointed out that the pandemic has highlighted the importance of care work: the labor that goes into raising children, treating the sick, and helping the elderly. This labor has been underpaid and underappreciated in America for generations, even as it has kept us all alive. The pandemic, with its new definition of the “essential worker,” brought the importance of such workers to the fore, and while it has not yet redressed the harms done to them over decades of marginalization, it has at least gotten more of the people who depend on them to listen to what they’ve been saying.

I am thinking, though, about more than care work these days, when I am able to think at all. I am thinking about care writ large. The historian Jacob Remes recently told me that the pandemic should prompt a reorientation of our society around an ethic of care, which would involve not just the fair compensation of child and elder care workers, but also an acknowledgment that all of us have care responsibilities in their lives.

This is true of the child-free as much as it is true of parents. Some of us are caring for children; others care for partners or elders in our families; each of us has the task, more difficult than it used to be in a time of disease and danger, of caring for the self. All of these responsibilities are important, even sacred. I want us to acknowledge the ways in which our duties of care divide our attention from our work. I want us to be able to make this acknowledgement safely, without getting fired or sanctioned. I want it to be central to the way our society operates, from parental leave to pay equity to the relationship between employer and employee to the very way we think about work in human life.

It’s not that I miss writing in lockdown. I am privileged in that on good days, I like my job, and I enjoy being able to do it without distraction. I wrote part of this essay when my son was home with a cold, and part of it when he was at daycare, and the second part went much more quickly and required less editing after the fact.

I also understand that to view the competing demands of parenthood and work as a matter, primarily, of attention is itself a luxury. Many front-line workers have had to choose between paying the rent and caring for their children in the last two years; that choice is a lot harder than trying to work while your kid yells at you through the door.

But for myself, at least, I’m trying to see the divided focus that caregiving brings as signal, rather than noise. I’m letting it remind me that no one was ever only a worker, despite what our employers might want us to believe. I’m letting myself imagine what could be if we remembered that we are all humans who raise and heal and shelter one another, and that this capacity exists not independent of whatever else we do with our minds and hands, but alongside it, intertwined and inextricable, forever.

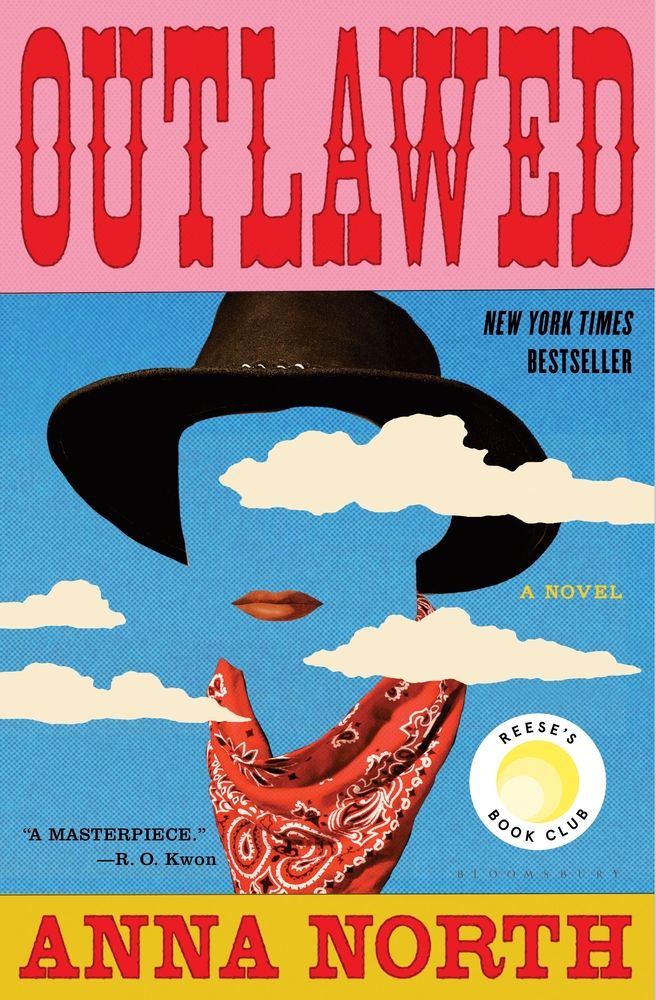

Anna North is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and the author of three novels: Outlawed, a New York Times bestseller; America Pacifica; and The Life and Death of Sophie Stark, which received a Lambda Literary Award in 2016. She has been a writer and editor at Jezebel, BuzzFeed, Salon, and the New York Times, and she is now a senior correspondent at Vox. She grew up in Los Angeles and lives in Brooklyn